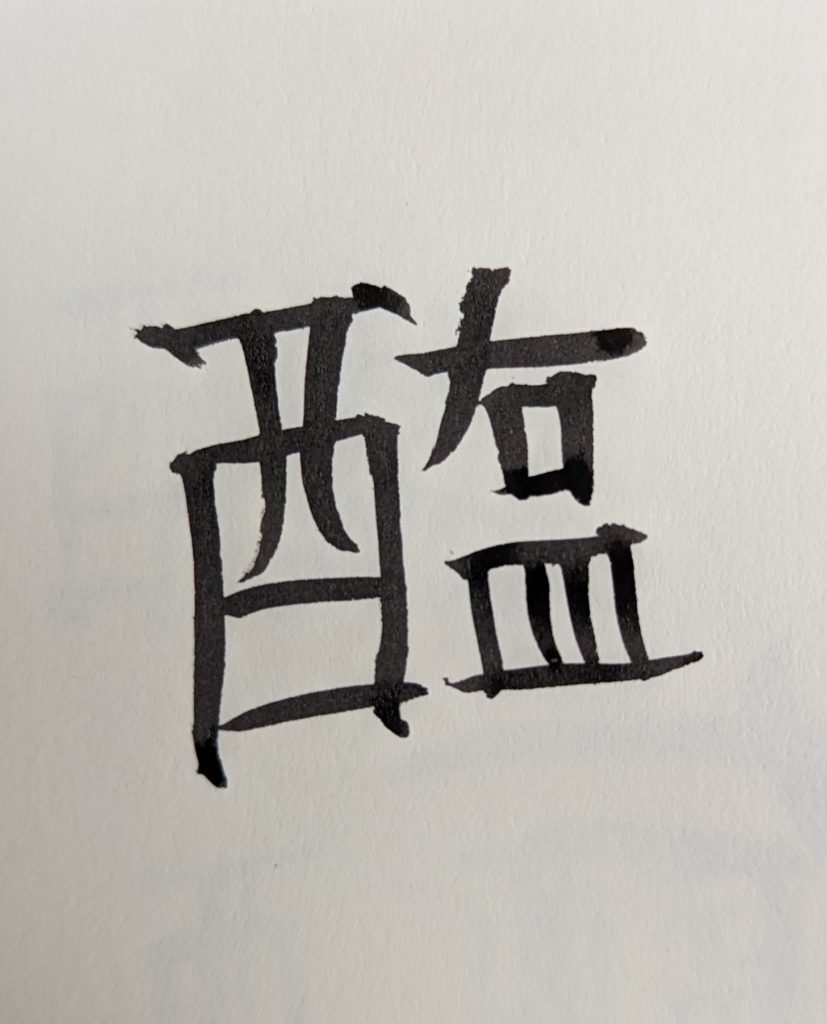

I recently read Hai, the final story in Yan Ge’s collection “Elsewhere”. It’s a visceral depiction of the vicious politics of Confucius and his successors. Hai refers to the practice of executing someone by chopping off their flesh, and mincing them alive. Then feeding it to their father as punishment.

Both history and myself are a bit vague on the world inhabited by Confucius, Lao-Tzu and Zhuangzi. It was a time of many states warring against each other, but bound by a common, literate culture (the “Xia”). “Troubled times inspired a spirit of enquiry and a predisposition towards novel solutions” (China: A History, John Keay). People could move around the states, looking for success. Unsuccessfully, in Confucius’s case, at least in his lifetime. This was the world of “personal detachment, emotional vacuity, various physical disciplines and a back-to-nature primitivism” (ibid) that has become the grounding for various modern practices. Not least Tai Chi, which in turn becomes a grounding for how I go about my daily life 2500 years later.

Putting aside the relative modernity of many of the “traditional” martial arts, this is at least the history that’s in mind when we put ourselves through the grind of practice. And it wasn’t very peaceful. It’s fair to say the wisdom was born from traumatic times, albeit themselves looking back to a semi-mythical history, whether the earlier days of the Zhou dynasty, or before. That turmoil was politically complex and sophisticated.

What’s prompted these thoughts? At least, it’s wanting not to pretend that there were other times when these arts were easier, when life was simpler. It’s recognising that, despite the modern world of “knowledge workers”, where the brain is wrung out daily, there was probably a fair amount on most people’s minds in ancient China. And perhaps, what’s not often admitted by the arts (but is by observers), they are mostly available as a luxury to the privileged. Itinerants would surely have toured the states to make their name, to gain favour and sponsorship, from those with power. And still, time and training is costly. Access to quality training is rare. Discernment is essential. Life is messy and unforgiving.

This all boils down, for me, to recognition and reassurance – which is perhaps why we look to history in the first place – to see what continues to be true, and at the same time to clear away any fog of idealised romance.